Atlas knows messaging wins battles. That’s why they train for it.

The Atlas Network hold strategic communications workshops to make sure they can sway public opinion through messaging. That’s how they make cruelty sound like common sense in the eyes of the public, thats how they help National ACT and New Zealand First win votes. Most people on the left are still unaware of the importance of messaging. Some find it boring. But if we don’t get better at messaging, we will keep losing no matter how good our policies are.

This article breaks down exactly how Atlas does it, and more importantly, how we can push back. Not by lying or spin like the right do. But by learning how to communicate clearly, effectively, and with purpose.

Read it. Share it. Practice it. Show it to our left wing politicians. Because if we don’t take this seriously, Atlas will keep shaping the narrative.

Market Your Brand (of policy)

Right now, you’re probably reading this on a phone or a computer, these are devices that were once seen as fringe, experimental tech, even radical ideas. But today they feel essential.

Just like technology, political ideas move from the margins to the mainstream by being framed as necessary solutions for everyday life such as health care, education, worker rights.

Look back just over a century and you’ll find workers being arrested and even killed for demanding an eight-hour workday. At the time, that demand was radical. Employers and Governments cracked down on the strikes and often violent battles would occur.

And yet, today, the eight-hour day is considered completely normal — even necessary.

So how did this happen?

While the protests, strikes and battles were certainly critical, as they propelled the issue into public consciousness. It wasn’t just confrontation that made the eight-hour day stick. It was also messaging work: unions framing it as reasonable, popular media slowly reflecting it as standard, legislation enforcing it, and generations growing up expecting it. Employers eventually adapted their business models around it, and today, even right-wing politicians rarely dare to say we should go back to 12- or 16-hour workdays.

Radical ideas become normal through persistent framing, repetition, and making them feel like common sense.

Personify The Abstract

Recently former National party finance minister Ruth Richardson was on Q and A with Jack Tame where she - speaking on the “causes” of the Taxpayers Union - says “we are on the side of Tim the taxpayer” ¹

This is a framing approach that avoids abstracts, it is one of the reasons Taxpayers Union so easily swayed people with the anti 3 waters campaign, if you give your ideology or goal a face, people empathise with it more.

While the left clearly are more compassionate than the right, unfortunately our language is too anodyne and abstract. Saying “nurses are overworked” is technically true, but emotionally distant. It doesn’t make the audience feel anything. It’s depersonalised, passive, and easy to ignore. However, if you put a name to it, say “Jane the nurse and her co-workers are underpaid and burned out due to understaffing” you generate much more emotion out of the public.

This was common during labour struggles in the early 1900s, domestic and international figures like Fred Evans and Joe Hill personified the struggle, it worked because people are more likely to follow people than abstracts.

Importantly, this shouldn't be about turning people into symbols. It’s about refusing to let real lives be reduced to data points and abstracts, because every policy, every profit margin, affects someone’s actual life.

With their language, the right personifies abstractions—treating corporations as people (think ‘corporations are job creators’ or ‘the free market will provide’)—while the modern left’s language unintentionally turns people into abstractions (‘the working poor,’ ‘marginalised communities,’ ‘beneficiaries’). This allows the right to consistently get away with stripping rights from people while granting more rights to profit-driven entities. We on the left must break out of this habit if we are to reconnect politics with real lives.

Speak Their Values: How to Sell Leftist Policy Across the Divide

Labour Party leader Harry Holland was a Marxist. The concept of surplus value became a recurring theme in his speeches and writings, and one of his lectures on the topic was even published as a pamphlet. His reading was wide, and in his later years, he turned to the writings of Lenin and Trotsky as they became available in English. ²

Holland helped transform the New Zealand Labour Party into the second largest party in 1926, surpassing the Liberal Party. ³

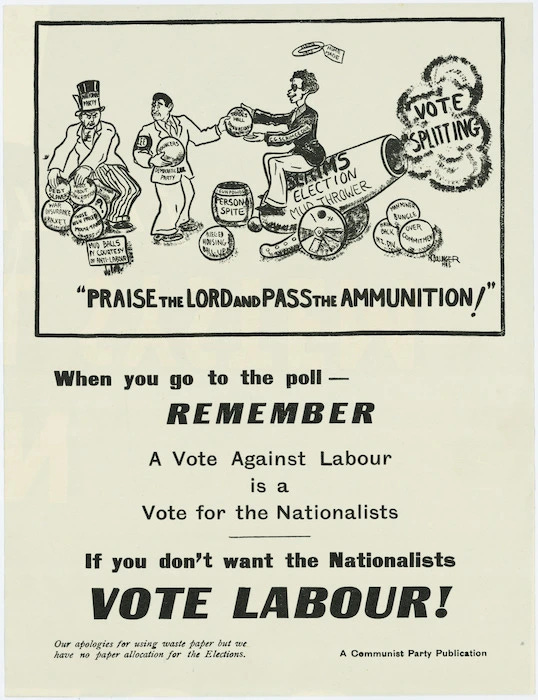

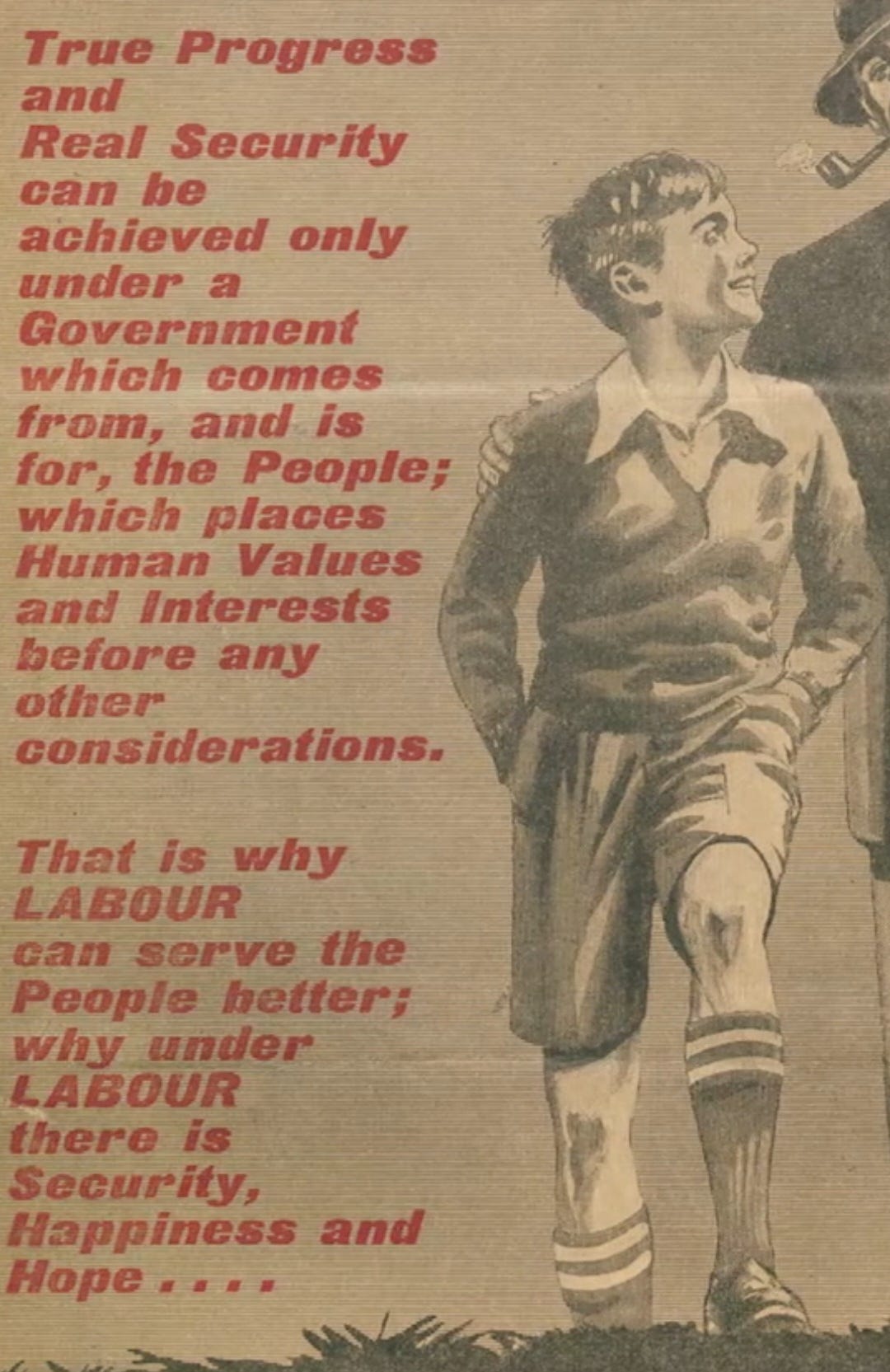

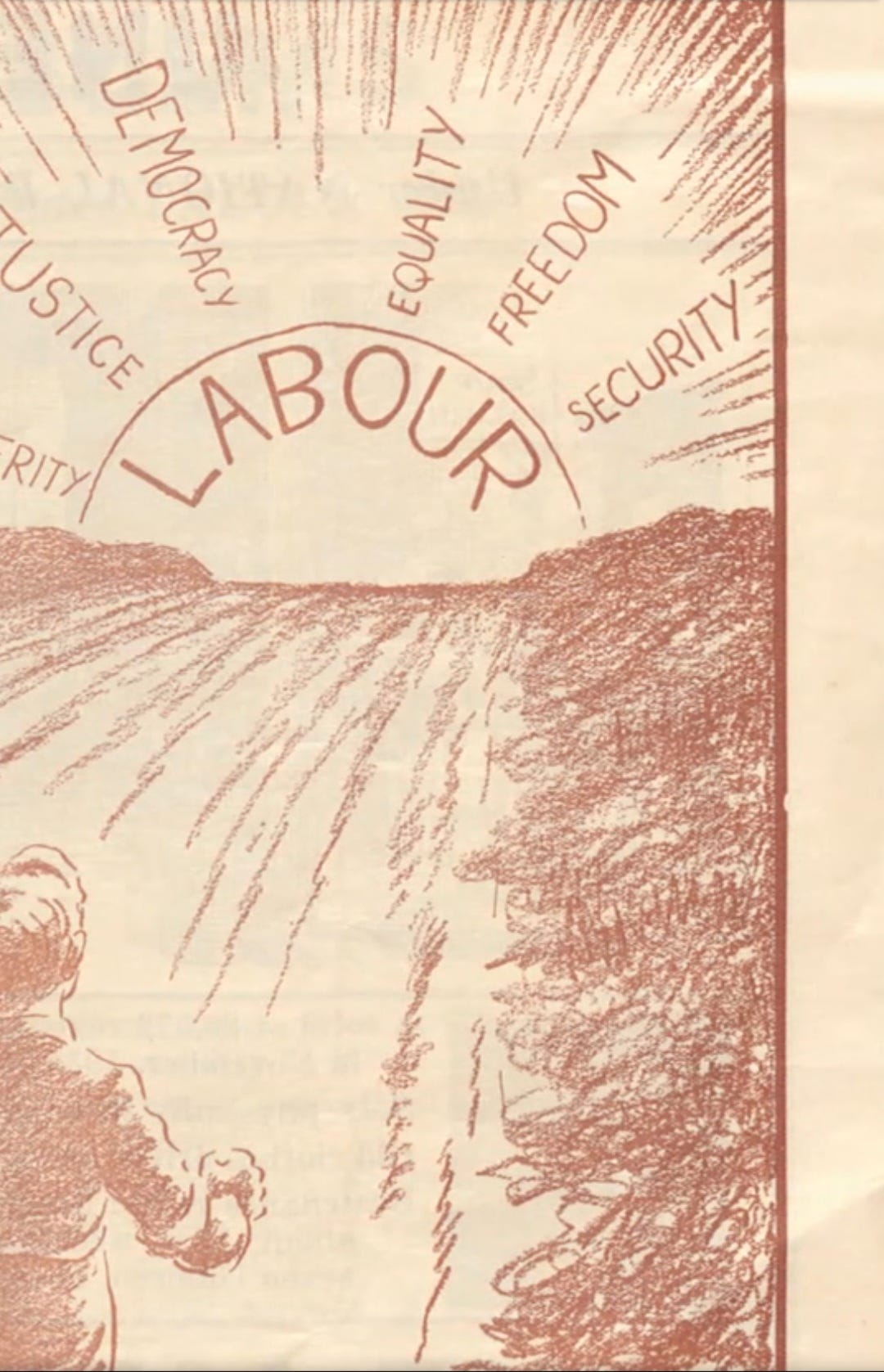

In 1943, the Communist Party of New Zealand published Labour Party election posters

And it worked—The election saw the governing Labour Party re-elected by a comfortable margin. ⁴ Far from scaring voters off, the visible presence of Marxists and Communists still led the Labour Party to succeed. Bold, leftist policies were framed in ways that connect across ideological lines—not by compromising, but by communicating.

The right loves words like ‘security’, ‘ambition’, ‘freedom’, and ‘prosperity’. The left has better answers to those values—we just need to say so.

Here are some examples of pre-neoliberal Labour doing it well:

In modern times this can work with many policies. Take Universal Basic Income.

UBI should be framed not as a handout, but as ‘security that rewards ambition’

This framing appeals to the center and the right who believe in “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” rhetoric while also appealing to progressives who advocate for more equity.

The ideas aren’t the problem. The language is. And language is something we can reclaim.

The right frame things like unions, benefits, or fair pay as luxury, we need to frame it as necessity. For example a good slogan for justifying and creating demand for fair pay would be - “Fair pay, your launchpad, not your safety net” as once again it appeals to ‘ambition’ and ‘security’ while being a left wing policy. By calling fair pay a “launchpad,” the slogan says: fair pay is not some optional extra or charity, as the right want to frame, but the essential starting point everyone needs to build their future and succeed. That makes it sound like a practical, necessary condition for ambition and security, not a handout.

This doesn’t just work for parliamentary politics — it applies to treaty-based governance and radical movements too.

Take communism, for example: Introducing it as “the doctrine of the conditions of the liberation of the proletariat” is too academic.

Calling it “classless, moneyless, stateless” sounds too utopian.

And “dictatorship of the proletariat” is off-putting, even if you understand the theory behind it.

But “from each according to ability, to each according to need” is more resonant, clear, and a principle nearly everyone can get behind

Libertarian socialism can be introduced as “economic democracy”

Anarchism as “Power with, not power over”

Co governance as “shared stewardship”

If we want these ideas to spread, it is integral that they need to be truthful and accessible when we introduce them.

Crisis or Sabotage?

Money doesn’t just “flow” by itself — people decide how it’s used. So calling the recession that National have caused, an “economic crisis” makes no sense politically; “crisis” sounds natural, like a tornado or earthquake — a random disaster. The accurate framing is “economic sabotage.”

Saying “National made you lose your job” sounds like a passive accident. But when you lose something it is an unintentional misplacement, Losing something implies it’s gone missing by mistake, but you know where your job and your house is, you never lost them, They were stolen away from you by National.

When we hide who’s really responsible, the story loses its impact and empathy. If the person who “lost” their job is the only focus, and not the actor (Luxon and the rest of the coalition) people subconsciously see it as an individual failure instead of a political attack.

National like to tell people that the previous government did so much “wasteful spending” but that’s a misdirection of how economies work. The word “spend” sounds like something’s being used up and lost, but that’s not what happens when governments fund public services. When money goes into things like unemployment support or healthcare, it doesn’t vanish — it goes directly into people’s pockets, gets spent again in local businesses, and keeps circulating. Far from being wasteful, this kind of investment actually strengthens the economy while meeting people’s basic needs. National’s approach on the other hand often involves giving money to the wealthy, who may hoard it or stash it in tax havens. When money is taken out of circulation like that, it doesn’t return to the economy or support public services. This kind of behavior fits the true definition of wasteful spending—using resources carelessly or to no purpose because the funds disappear from productive use.

Here’s a great video from UK Labour from 2019 making this point: ⁵

Visible Solidarity

During the 1981 Springbok Tour protests, helmets were a common sight. They showed a generation of New Zealanders willing to put their bodies on the line to oppose apartheid. And importantly they showed visible solidarity.

Visible solidarity such as the Black Panther Party black berets, or the Springbok Tour protest helmets show that this is the dominant belief structure, normalising it. That is why the Springbok Tour protest is so significant. Most people today can easily picture what an anti-apartheid protester looked like in 1981 — but ask them to visualise a counter-protester, and it’s much harder. The protest became the symbol of national conscience. It defined the moral centre despite being one of the most radical and violent events in New Zealand’s recent history.

Speak to voters in terms they can picture.

When we talk about wages, it makes more sense to frame them as the share workers get for the value they create. Wages are the slice of the profits workers help generate. So, when we talk about how wages have changed, we need to talk about the people behind those numbers. Put simply: “Over the past 30 years, Kiwi workers have been getting a smaller and smaller cut of the wealth they create, being left with little more than crumbs.” This usage of words conjures an image in peoples heads of a pie that workers have contributed to making but don’t get their fair share of.

The right know full well the public wouldn’t back them if they were honest about their intentions. No party’s going to campaign on polluting our rivers, cutting down native bush, or gutting our public schools — because they’d never win. So instead, they wrap harmful policies in vague slogans and PR spin. We need to name them repeatedly what they really are.

Here are some examples:

The Regulatory Standards Bill as The Democracy Erosion Act

The Social Security (Mandatory Reviews) Amendment Bill as The Poverty Trap Tightening Act

The Public Works (Critical Infrastructure) Amendment Bill as The Forced Land Theft Law, and so on.

It is important to practice repetition of this framing, it works in our favour because the original names of these policies are so dull and forgettable, only our clear blunt framing will stick in people’s minds. When we keep calling it the Forced Land Theft Law, that’s what people remember. Repetition is power, it engages our base and convinces the middle with a morally grounded message.

Don't Think Of A Giant Moa!

When the coalition government was targeting pay equity National kept denying they were cutting it. This was pointless however because when National says, “We’re not cutting pay equity,” the frame still activates the idea of cutting pay equity — because the brain processes the concept, not the negation.

It’s like saying “Don’t think of a giant moa.”

You just did.

The image is now alive in your head, even though the moa hasn’t been around for centuries. That’s exactly how negative framing works. The same works with policies, when they say, “It’s not the Democracy Erosion Act,” they’ve already lost. They’re repeating our words, reinforcing our frame, and keeping our message in the public mind.

With. Not For.

During the 2023 election the New Zealand Labour Party ran with a… less than inspirational slogan, “In it for you”

It came across as paternalistic, implies voters are recipients, not active participants, sets up a separation between “them” (the leader/the party) and “you” (the voters), rather than shared purpose.

“In it with you” would have been much better, it signals partnership and shared effort, messaging needs to be inclusive “it's you and I together who will face down inequality” to be effective. We on the left always talk about trying to get people involved in democracy. It needs to show in our slogans and our rhetoric.

In conclusion

This is about telling the truth — but doing it in a way that actually reflects our values and connects with the public. Too often, progressives avoid framing altogether, or worse, use technical language that no one relates to.

Meanwhile, the right keeps repeating simple, value-loaded messages. We can do the same — not by lying like the right do, but by being clear about what we stand for and explaining it in an accessible way. Framing should never be dishonest — not just because that’s wrong, but because it doesn’t work. Sooner or later, people see through it, and you lose trust.

We don’t need to manipulate to be effective. In fact, some of the strongest wedge issues are already grounded in shared values, things like clean water, public healthcare, or decent pay. These are basic things that most people agree on. When we talk about them using accessible terms through the lens of fairness, security, wellbeing, and community, we’re leading with the truth, and giving people a reason to stand with us.

And finally we need to be unapologetically left. A real movement needs all kinds of voices — including those who are unapologetic and uncompromising. Progressives need to stop mumbling in the middle of the road as Labour does all too often and actually be unapologetically left, with better messaging, because it works. Labour needs to stop attacking Te Pāti Māori and Greens by calling them "unrealistic" and "stupid" because not only are they enabling the framing from the right, but even their own 2017 messaging strategist Anat Shenker-Osorio — founder of ASO Communications, whose messaging strategy helped Jacinda Ardern win the 2017 election despite only having seven weeks to prepare backs this up.

In her book, Don’t Buy It: The Trouble with Talking Nonsense About the Economy — a massive inspiration for this article, Anat Shenker-Osorio wrote:

“Regardless of what we do or say, our opponents will call us wildly out of touch and wacky, so we might as well have some fun and say what we actually mean. It’s shockingly difficult for us to speak from our worldview, accustomed as we’ve become to walking the fictional middle line. We’re losing so much ground in every battle, it feels scary to “go out on a limb” and come out swinging for what we believe. But make no mistake: continuing to do the same things and expecting different outcomes is a madness we don’t have the time to indulge.” ⁷

Sources and references:

¹ Ruth Richardson: Super age should rise, assets sold | Q+A 2025

² Harry Holland | Australian Society for the Study of Labour History

³ Harry Holland Wikipedia Page

⁴ 1943 New Zealand General Election

⁵ Ordinary People Vs Billionaires – Labour’s party political broadcast

⁶ Convincing people that change is possible by ‘painting the beautiful tomorrow’

⁷ Don’t Buy It: The Trouble with Talking Nonsense about the Economy

Further reading:

I hope the left are reading this. Exactly what needs to happen. Love the pre neolibral poster......if only we could go back. Thanks Kaimaatara great read.

Thanks for writing this article. I have subbed.

I’m more of an educator than a public relations official. But the two can coincide I suppose. We must try everything at this point.

I agree that there are serious framing issues, and want to add some other suggestions:

“cost of living crisis” → “price gouging crisis”

(depoliticized into politicized)

“independent think tank” —> “dependent think tank”

(say who its dependent on. There is no such thing as a purely ‘independent’ institution.)

“liberal democracy” —> “late stage plutocracy”

(strong evidence for this!)

“independent central bank” -→ “technocratic central bank”

(strong evidence for this!)

“natural rate of unemployment” > “unchosen policy for unemployment”

(unemployment is the result of policies, not ‘nature’).

In my view. most corporate propaganda and its language generally aims to be depoliticized, (not mention the politics behind it why the world is like this). This prevents people from understanding the political system and how they are being attacked. That’s the position that austerity economists took in the 1920’s until today. (clara mattei wrote a good book on this).

In general I think political education needs to be like all other education. It needs to say something insightful and interesting, to motivate interest in politics. It also needs to be done in a way that generates respect from people with different views. Such respect can be gained in all sorts of ways. Like showing proof of sacrifice, ability to care about what opposing groups think and talk to them, etc.

And it needs to envision a future society and show an outline on how to get there.